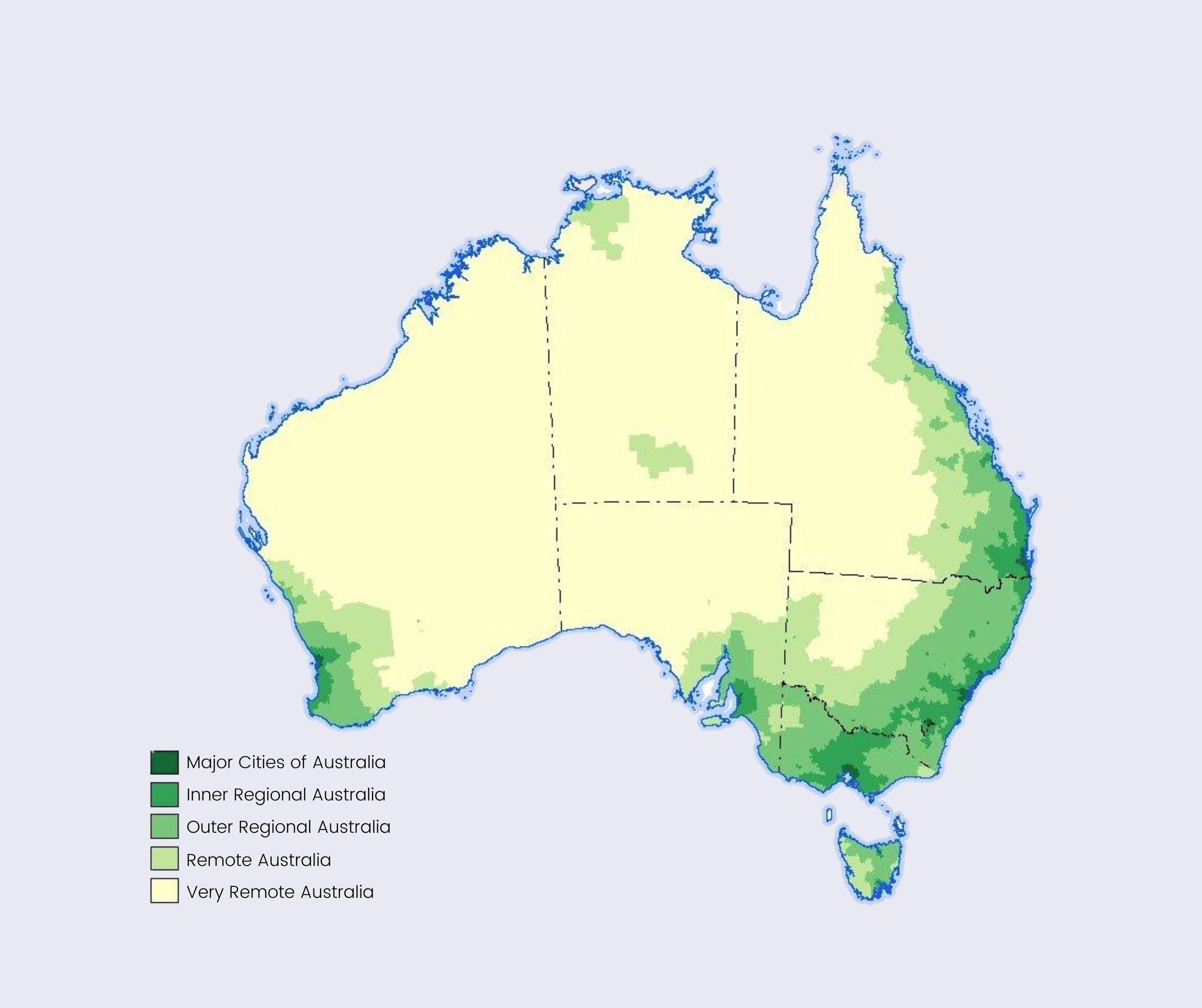

NDIS Services in Rural and Remote Australia

Australians in regional and remote areas face significant geographical barriers to accessing adequate health care, with data showing that this population group has higher rates of hospitalisation, injuries and death than people in major cities.

Slimmer services make sense in the outback, as Australia is the third most sparsely populated country in the world. But vast distance shouldn't compromise equal access to healthcare and NDIS services in rural areas.

Some statistics

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, for every 100,000 people, major cities have 44% more medical practitioners and 28% more allied health professionals than very remote Australia.

Around 55% of this allied workforce are NDIS registered providers in remote and very remote Australia.

28% of the Australian population, roughly seven million people, live in these rural and remote areas.

44% Indigenous Australians live in regional areas and 21% in remote communities. Indigenous Australians are 1.5 times more likely as non-Indigenous Australians to have a disability or restrictive long-term health condition. As of March 2022, there were 37,313 First Nations NDIS participants, and roughly 10% live in remote locations.

Rural and remote populations clearly face significant challenges accessing healthcare, but why is this particularly a problem for NDIS participants?

Choice and control

The NDIS was designed to give participants choice and control over their supports and services. If there aren't many providers (a thin market) choice and control are limited.

Thin markets is a term to describe insufficient market types. It applies to the NDIS market in rural and remote Australia as the service base is too shallow to incentivise provider competition, with no choice a common outcome. NDIS providers are inundated and unable to meet demand, and long waitlists compromise participant safety and can worsen conditions.

The other fundamental value of the scheme is control. Control as a participant, whether self or plan managed, includes fully understanding your plan to best achieve your goals. Public Hearing 25 heard experiences of First Nations people as part of The Disability Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability.

Joan Houghton from Alice Springs comments on the struggle to access the scheme, including difficulties obtaining functional capacity assessments and an explanation of the scheme in a First Nations language.

‘Being able to explain that in language, through concepts, through construct in terms of pictures so that people can really understand what's happening for them. And to have them design it as well. They need to be able to consult with the communities themselves around what are the priorities for the community and how will it - how can things change for them.’

Joan cares for two Indigenous children with disabilities in Tennant Creek. One of these children, Joziah, has various disabilities resulting in full reliance on a wheelchair for mobility. She says the NDIS could have better assisted other organisations and the Health Department to ensure Joziah received physiotherapy.

‘He wasn't receiving physiotherapy because of the fact that he was unable to access it at the location where we were in terms of Tennant Creek because of the intermittent service delivery, and the local ACCHO - which was the community health organisation, the Aboriginal one - wasn't being able to deliver allied health because of they had different funding.’

NDIS participants in rural and remote communities often receive sufficient funding, but the locations need more infrastructure and workforce to deliver. If a participant's plan is under-utilised (even if due to thin markets) they may struggle to justify or not receive the same amount of funding in their next plan.

University of Melbourne's report determining inequalities for people living with disabilities identified residents in remote Victoria were receiving smaller NDIS plans than their urban participants. They were also less engaged with services and less able to spend the allocated plans, resulting in an underutilisation of funding.

Barriers to access

Remote location or not, accessing the NDIS is an undertaking in itself. The financial, time and emotional toll of proving your disability is more trouble than it's worth for many. Gathering evidence to create a case for your plan, accessing specialists, financing an occupational therapist to write a functional capacity assessment.

42% of young people with disabilities and their families face barriers to getting on the NDIS. In submissions to the Children and Young People with Disability Australia survey, submissions reported lack of available services was the main barrier to accessing supports and services, followed by an NDIS plan not allocating for services they require and extensive waiting lists.

It's worth acknowledging across First Nations languages, there is no word for disability.

Indigenous communities have always had an inclusive, 'social model' of disability approach. People with disabilities weren't excluded from their mob, with the responsibility of their care vested on the community or family, not the individual.

The Royal Commission acknowledged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people focus on individual strengths and differences rather than deficits, which may be difficult for individuals applying for the NDIS, asking them to do just that. The Kimberly Stolen Generation Aboriginal Corporation explains:

‘If someone is born with a physical disability or may have a mental health issue, the community usually treats this person no differently than they would treat others but understands that they may need extra help from time to time.’

This different perspective may result in a lack of understanding of the concept of disability against a western system, Jody Barney a Deaf Aboriginal/South Sea Islander woman notes:

‘The reason I say that is the system is western in cultural view... It's a western system. It's a mainstream system. It doesn't give thought to the layers of culture that people have. Not only for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people but also for Deaf people. So those cultural barriers that people encounter, you can see that there's really a double disadvantage.’

Cultural competence

There are at least 55 First Nations sign languages. Jody Barney provides language support and access to the NDIS, court and other health environments for First Nations people who are hard of hearing. Jody is able to communicate in 20 of these languages.

She speaks honestly about the distrust between Government services and local communities as another system focused on deficit, diagnosis, and bureaucracy speak.

‘It's just another system that controls what they do, that tells them where to go, who they can have contact with, what they must do, who can provide services to them. I know a Deaf person who has never had a hearing aid, has never used English, has never had speech therapy and now their plan is including conditions that is forcing them to go to speech therapy.’

Jody notes it isn't all bad, wonderful teams are working within the NDIS committed to ensuring their approach is accessible and respectful. But there needs to be great cultural competence for or most disadvantaged in the system.

‘We are talking about people who have complex language needs here. People who have other issues with the justice system or with housing, or with mental health or unemployment where it becomes more controlling from the NDIS in trying to think about what's best for them or people who have responsibilities to care for that individual think they know what's best.’

So, what has been done?

The Department of Social Services (DSS) and the NDIA have commissioned a project in 2019 to develop strategies to address supply gaps in rural thin markets. In November 2022 the NDIA wrapped up their Aboriginal Disability Liaison Officer (ADLO) program which will contribute co-design initiatives in how the scheme operates in Indigenous communities. There are is also Rural and Remote Strategy, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Engagement Strategy, Cultural and Linguistic Diversity Strategy and the Community Connecters Program in the pipeline.

We’ve identified the barriers to accessing health care in rural and remote Australia, why thin markets impact the purpose of the NDIS and the need for greater cultural competence. Rather than chew your ear off some more, in the next blog post, we will discuss what we think needs to be done to create a better experience for NDIS participants in regional and remote Australia.